How to Read an Editorial Letter

With special guest Julie Scheina of Your Editor Friend

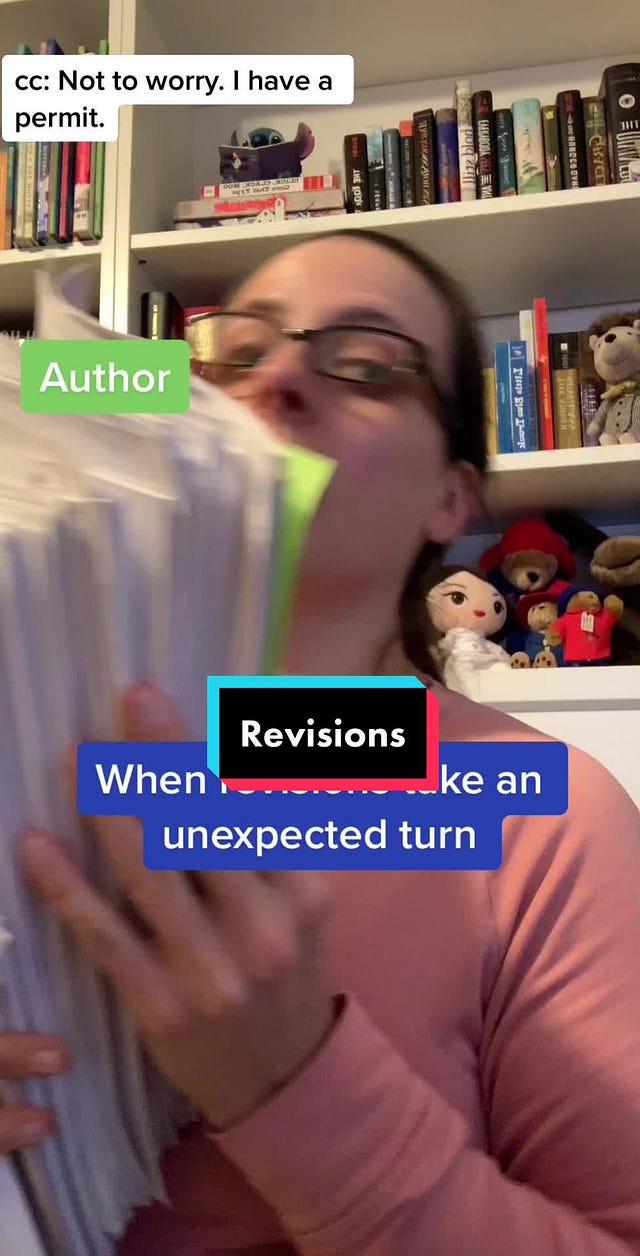

Greetings from revisionland!

Well, several predictions I made in the last podcast episode have come to pass: MFA residency prep took over my holidays, I caught COVID at said residency (I’m okay), and I got editorial notes on the final revision of my next book.

How do I know this is the final revision? I just know. There will be a round for line edits and copyedits, but I’ve been through this enough times to know what phase I’m in when I’m in it.

I thought I’d take the procrastination opportunity to talk about how I deal with editorial letters, which are documents from a book editor that exist to guide the writer through a given draft. They vary in length and form depending on the editor and depending on where you are in the process. They might be from your in-house editor at the publisher where your book is contracted, or they might be from a freelance editor you’ve hired, or they could even be detailed notes from a beta reader.

That’s the technical, unemotional definition.

But the editorial letter can be freighted with less tangible meaning for an author. We read between the lines for answers to the questions: does my editor hate my book or hate me, have I exhausted them to the point they’ll never want to work with me again, does this book have a chance, did I do good, am I good? Mommy? Daddy?

Because the letter can carry these projected existential concerns, it—like any feedback—sometimes must be approached with both caution and courage.

I’m going to run through my process with The Letter, and I’ve invited Julie Scheina of Julie Scheina Editorial Services (and the editor for two of my books when she was at Little, Brown), to weigh in with an editor’s perspective.

Acknowledge receipt

This part’s easy. You see it in your inbox, and you reply, “Thanks, got it!” or “Can’t wait to dig in!” or “Great! More soon!” or some other enthusiastic confirmation that it got to you.

Julie says: The acknowledgment may seem pointless, but from the editor’s end it helps avoid constantly refreshing our inboxes wondering if the letter is stuck in spam somewhere. In my experience, it also helps to dampen the same type of projected existential concerns mentioned above (Does the author hate me or my notes, are they too apoplectic or devastated to even acknowledge receipt, do they never want to work with me again?).

Cooling off period 1

The amount of time I let it sit in my inbox unopened varies. I need to assess my emotional and practical readiness to receive in-depth information about my work. If I’m overwhelmed with other tasks, know I won’t be able to work on my revision for a while anyway, or hormonally compromised, I just leave it alone.

Julie says: Revision readiness cannot be understated. If you’re not in the right state of mind to think critically and deeply about your work, considering any type of change can feel impossible. If you get your edit letter at the end of a particularly exhausting day, give yourself a chance to recharge before diving in.

The first read

When I’m ready with a clear, calm mind, I read the letter. My editor tends to write very dense, long paragraphs, so I like to export the letter into an epub and read it on my phone in a nice big font as though it’s a library book. As I read, I highlight key points and get the gist of the scope of the work to be done.

Julie says: Other methods I’ve heard for this step include printing the letter with extra spacing so that you can add your notes alongside the editor’s and ranking the changes (e.g. A: I immediately agree; this is a relatively simple change; B: I agree; this is a more complex change; C: I’m not sure if I agree; I need to consider this more; D: I disagree; I need to respond and discuss). These rankings might change as you give the notes more thought in the next step, but they can offer another gauge for the amount of work involved.

Cooling off period 2

Before I react to or act on the letter, I let the contents of it tumble around in my mind. This might last a day or two. During that time, I do dishes and put away laundry and think consciously about the letter. Ideas for problem-solving are already percolating at this point, and I’m getting excited to sit down and do the work.

Julie says: This step is essential. It can be tempting to want to jump in right away, but rushed revisions are often less cohesive, more superficial, and require more work in the long run than those that are made after some reflection. Taking this time also helps you to continue identifying which suggestions are resonating with you and which need more thought. Don’t be afraid to use the suggestions in the letter as an initial jumping-off point to brainstorm other solutions.

The second read

I read the letter again. Sometimes, I rewrite it into my own bullet points to clear away the weeds, which might be in the form of my editor’s niceties. My editor on this book is from the “gentle and encouraging” school, so sometimes there’s a bit of padding that makes it all easier to swallow but then needs to be shaved off for clarity.

Julie says: Many authors tend to skip over any praise in editorial letters. While this makes sense when you’re ready to get down to work, I’d love authors to read them during the above steps—not just to tamper the feeling of “my editor hates this book and everything needs to change,” but also to clarify what is already working well in the current draft and hopefully won’t change as you revise.

The “more soon”

Now I respond to my editor properly to make it clear that I’ve dug into the letter and comprehend the scope. If there’s any confusion or disagreement about what’s to be done, I bring it up here. I also make an educated guess about how long I expect the work to take. For a contracted book, this is usually a “yes I can make your deadline, I think,” or “I may need more time” conversation. With a freelance editor or peer, this conversation might be about setting personal goals for your next steps.

Julie says: Depending on how you like to work, phone calls can be helpful for bouncing ideas off your editor, getting clarity on any confusing points, and hashing out other tricky areas in real time. Some of my favorite and most engaging conversations with authors have happened during these stages. If necessary, you can also send your editor a recap of the conversation to ensure you’re both on the same page before you dig in.

(Note: My current editor and I often have this conversation before he writes the letter, but in any case making voice-to-voice contact is a good reminder that you are two humans who—hopefully—like working together!)

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Do the work!

I keep the letter (in its non-threatening epub form) and/or my rewritten version of the letter nearby or open, and get to work on the revision. The actual execution of the notes is a different topic for a different day! First, I’ve got to execute mine.

📫 Get Julie’s newsletter, Your Editor Friend.

🎧 I listened to this episode of Spark and Fire this morning while waking up, and Ann Patchett’s insights about her process made me want to get out of bed and write!

👀 Nevermind that this Elin Hilderbrand thing looks like it was probably a superspreader event—it got me thinking about what a weekend conference designed around the world of my books would involve. I would probably rent out a big commercial kitchen, have a set decorator transform it into several domestic kitchens, and then encourage people to have tense conversations while serving meals and/or coffee. Is there an author whose world you’d want to spend a weekend away in?

This Creative Life is a book, a newsletter, and a podcast from me, Sara Zarr, about reading between the lines of a writing life. The newsletter and podcast are free; buying the book (and leaving a great review!) helps support them and me. Sharing the newsletter is a big help, too!